“Remember the Alamo”. That was the war cry that started with the brave men of Sam Houston’s Forces that fought the Mexicans at San Jacinto for independence from Mexico. It came about following the defeat of the Texians (American settlers and illegal immigrants) at the Mission San Antonio de Valero later to be known as “The Alamo”. The Battle of the Alamo lasted just 13 days from 23rd February to the 6th of March 1836 where the troops of Santa Anna fought a force of Texians seeking independence led by Colonel James “Jim” Bowie and Colonel William Travis. Also involved in this battle was legendary Tennessee Pioneer Davy Crockett. All but half a dozen or so non-combatants died or were executed during the siege.

These days there is little of the entire Mission San Antonio de Valero (built in 1718) remaining as the growth of San Antonio devoured what there was of the mission. Now the globally recognised façade of the Church and the church grounds is all that is left of the Alamo. Fortunately it and the nearby 4 missions are all World Heritage Listed and safe from further destruction. To read more about the Battle of the Alamo click here. Within the church grounds there was a “Living History encampment” where several people were dressed in period costume of the 1800’s who happily chatted to tourists like ourselves about those times.

All the notes below are from the US National Park Service site https://www.nps.gov/saan/index.htm

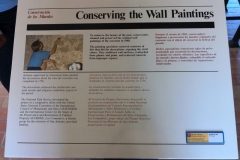

Next Mission out of town is Mission Concepcion (built in 1731). Dedicated in 1755, Mission Concepción appears very much as it did over two centuries ago. It stands proudly as the oldest unrestored stone church in America. In its heyday, colourful geometric designs covered its surface, but the patterns have long since faded or been worn away. However, original frescos are still visible in several of the rooms.

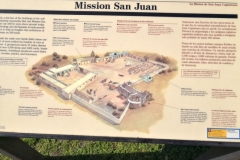

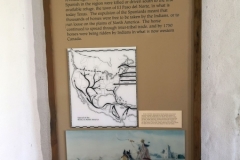

Mission San Juan Capistrano (built in 1731) Originally founded in 1716 in eastern Texas, Mission San Juan was transferred in 1731 to its present location. In 1756, the stone church, a friary, and a granary were completed. A larger church was begun, but was abandoned when half complete, the result of population decline.

San Juan was a self-sustaining community. Within the compound, Indian artisans produced iron tools, cloth, and prepared hides. Orchards and gardens outside the walls provided melons, pumpkins, grapes, and peppers. Beyond the mission complex Indian farmers cultivated maize (corn), beans, squash, sweet potatoes, and sugar cane in irrigated fields. Over 20 miles southeast of Mission San Juan was Rancho de Pataguilla, which, in 1762, reported 3,500 sheep and nearly as many cattle.

These products helped support not only the San Antonio missions, but also the local settlements and presidial garrisons in the area. By the mid 1700s, San Juan, with its rich farm and pasture lands, was a regional supplier of agricultural produce. With its surplus, San Juan established a trade network stretching east to Louisiana and south to Coahuila, Mexico. This thriving economy helped the mission to survive epidemics and Indian attacks in its final years.

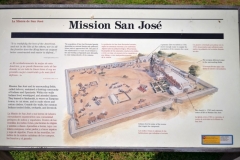

Mission San José y San Miguel de Aguayo (built in 1720). Known as the “Queen of the Missions”, this is the largest of the missions and was almost fully restored to its original design in the 1930s by the WPA (Works Projects Administration). Spanish missions were not churches, but communities with the church the focus. Mission San José captures a transitional moment in history, frozen in time.

Mission San Francisco de la Espada (built in 1731) This was the first mission in Texas, founded in 1690 as San Francisco de los Tejas near present-day Weches, Texas. In 1731, the mission was transferred to the San Antonio River area and renamed Mission San Francisco de la Espada. A friary was built in 1745, and the church was completed in 1756.

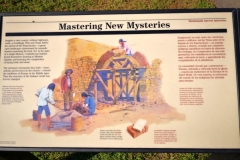

Following government policy, Franciscan missionaries sought to make life within mission communities closely resemble that of Spanish villages and Spanish culture. In order to become Spanish citizens and productive inhabitants, Native Americans learned vocational skills. As plows, farm implements, and gear for horses, oxen, and mules fell into disrepair, blacksmithing skills soon became indispensable. Weaving skills were needed to help clothe the inhabitants. As buildings became more elaborate, mission occupants learned masonry and carpentry skills under the direction of craftsmen contracted by the missionaries.

After secularization, these vocational skills proved beneficial to post-colonial growth of San Antonio. The legacy of these Native American artisans is still evident throughout the city of San Antonio today.

That’s it for San Antonio. I repeat what I have said before if you want a great place to visit then San Antonio really fits the bill.

As I type this we are in Galveston, Texas. And I have almost caught up with the blog posts. Anyway as I say each blog, watch for the next post.

Cheers for now

Garry & Shane